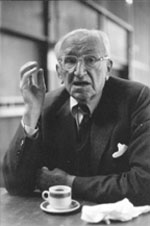

In the fall of 1918 a skinny boy-officer named Lieutenant Friedrich August von Hayek was falling back from the Piave River in Italy with the remnants of the Austrian army. He contracted malaria during the long retreat, but survived the Great War—returning to a Vienna that was no longer an imperial capital, but just an impoverished city of the tiny Austrian Republic.

From boyhood Hayek had loved botany and science, but now took he up economics. As he dryly remarked, "I served in a battle in which eleven different languages were spoken. It's bound to draw your attention to the problems of social organization."

Between the wars, Hayek alighted in England with a professorship at the London School of Economics. He befriended the charismatic John Maynard Keynes, but opposed him in an historic debate on the causes and cures of business cycles just as the world was slipping into the Depression. And, against the socialists in general, Hayek took up the argument of his mentor Von Mises that a "planned" economy is fundamentally unworkable.

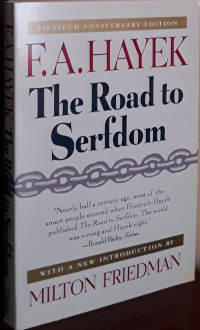

"I was known as one of the two main disputing economists ... Now Keynes died and became a saint; and I discredited myself by publishing The Road to Serfdom ..."1

In 1939 Hayek had returned to Nazi-occupied Austria for his summer vacation in the Alps. At forty he was still a vigorous and expert mountaineer, confident that even if war befell he could walk out of the country across the mountains. He did his best thinking there and it was then, perhaps, he decided to expand an article he had written into that "discreditable" book.2

His loyalty now was to England but, as Europe was swallowed up by totalitarians, he was beginning to wonder if his new countrymen really understood how easily their liberty, too, could slip through their fingers.

In 1944 he dedicated The Road to Serfdom to "The Socialists of All Parties," generously presuming that "they would recoil if they became convinced that the realization of their program would mean the destruction of freedom."3 Their schemes, he argued in this sober warning, had already led to tyranny in Germany and Russia, and good intentions would not save them.

In 1944 he dedicated The Road to Serfdom to "The Socialists of All Parties," generously presuming that "they would recoil if they became convinced that the realization of their program would mean the destruction of freedom."3 Their schemes, he argued in this sober warning, had already led to tyranny in Germany and Russia, and good intentions would not save them.

A year later he was astounded to find himself an instant celebrity in the United States. Instead of lecturing to a few professors he found himself addressing an overflow crowd in a 3000-seat auditorium. His talk was carried live on network radio. As Ayn Rand had recently discovered with the publication of The Fountainhead, there was a popular market for heterodox ideas about individual liberty, even if the intellectuals were less receptive.

The Nobel Prize came in 1974 for work done much earlier, but every year had been put to good use: fighting to retrieve and secure an ideal of individual liberty that the twentieth century had nearly swept away. And on into his eighties F.A. Hayek out-thought and out-lived the "socialists of all parties," an old soldier who had never given up.

— John C. LeGere

Copyright © 2000, The Daily Objectivist - Reprinted with permission of The Daily Objectivist and Davidmbrown.com.

9 Jan 2009 (last edit: 19 May 2025)

You can assist the work of Freedom Circle by purchasing one of the works discussed above:

-

Hayek on Hayek: Autobiographical Dialogue, Stephen Kresge and Leif Wenar (editors), London: Routledge, 1994, p. 90. (Freedom Circle note) ↩︎

-

A. J. Tebble, F. A. Hayek, New York: Continuum, 2010, p. 8. Tebble identifies "Freedom and the Economic System" (1939) as the earlier paper. However, on the same page Tebble states, "Unwilling to return to Austria after its annexation by, and subsequent Anschluss with, Nazi Germany in 1938, Hayek became a British citizen that same year", making the "Alps vacation" story doubtful. (Freedom Circle note) ↩︎

-

F. A. Hayek, The Road to Serfdom, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1944, p. 31. (Freedom Circle note) ↩︎