Civil Liberty and the State: The Writ of Habeas Corpus, by

Richard M. Ebeling,

Freedom Daily, Apr 2002

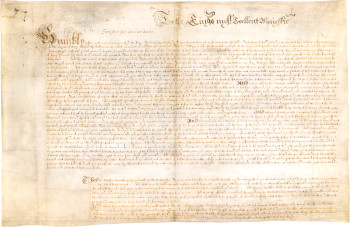

Highlights of English and American history on the writ of habeas corpus, in particular the 17th century conflict between Charles I and Edward Coke

When [King] Charles sent a message that he would respect the principles of the Magna Carta in general, Coke replied,

Did ever Parliament rely on messages? ... The King's answer is very gracious; but what is the law of the realm? That is the question. ... Let us put up a Petition of Right; not that I distrust the King, but that I cannot take his trust but in a Parliamentary way.

... Finally, the king gave in to a joint statement prepared by the Houses of Commons and Lords insisting that he accede to the two resolutions, and the Petition of Right was passed and read into the Statute Book.

The Third Amendment and the Issue of the Maintenance of Standing Armies: A Legal History, by

William S. Fields,

David T. Hardy,

American Journal of Legal History, 1991

Examines the history of quartering of soldiers in private residences and the maintenance of standing armies, both in England and the United States revolutionary and constitutional convention periods

Charles I had become involved in wasteful wars on the continent against France and Spain ... Parliament ... balked at subsidizing Charles' military ventures. With the king and parliament deadlocked over the issues of taxation and appropriations, large numbers of soldiers found themselves without barracks or money to pay for billeting in inns; and many were left with no choice but to seek quarters in private homes. The popular dissatisfaction which resulted under those circumstances found expression in the Petition of Right presented to the king by the Lords and Commons of Parliament in 1628.

Related Topics:

Standing Army,

United States Bill of Rights,

Edward Coke,

Thirteen Colonies,

United States Declaration of Independence,

England,

Patrick Henry,

James Madison,

George Mason,

New York City,

Philadelphia,

No quartering of Soldiers

The Third Amendment: Forgotten but Not Gone, by

Tom W. Bell,

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal, Jul 1999

Intends to fill "the most glaring" gaps in previous Third Amendment scholarship, including its connection to the property rights covered by the Fifth Amendment

For political reasons, the House of Commons refused to provide Charles I with adequate revenue for housing his troops, and as a consequence they sought quarters in private homes. In 1628 these circumstances led Parliament to complain, in the Petition of Right, that "of late great companies of soldiers and mariners have been dispersed into divers counties of the realm, and the inhabitants against their wills have been compelled to receive them into their houses, and there to suffer them to sojourn, against the laws and customs of this realm ..."

Related Topics:

American Revolutionary War,

American War Between the States,

United States Declaration of Independence,

Eminent domain,

England,

France,

London,

James Madison,

Magna Carta,

New York,

No quartering of Soldiers