Articles

China's Legacy: The Thoughts of Lao Tzu, by

James A. Dorn,

South China Morning Post, 4 Sep 2007

Contrasts the teachings of Laozi with respect to government intervention with the lingering effects of Mao Zedong's legacy

[Lao Tzu] argued that if governments followed the principle of wu‐wei (non‐action), social and economic harmony would naturally emerge ... The essence of this liberal vision is concisely stated in Chapter 57 [of the Dao De Jing]: "The more restrictions and limitations there are, the more impoverished men will be ... The more rules and precepts are enforced, the more bandits and crooks will be produced. Hence, we have the words of the wise [ruler]: Through my non‐action, men are spontaneously transformed ... Through my non‐interfering, men spontaneously increase their wealth."

Harmony: Lao-tzu, by

David Boaz,

The Libertarian Reader, 1997

First section of part four, "Spontaneous Order"; includes a brief introduction and short excerpts of five chapters from the

Tao Te Ching

One of the classic sources is the Tao Te Ching, thought to have been written in the sixth century B.C. by a scribe named Lao-tzu ... Tao is sometimes translated as "the Way," though another possible translation is "natural law." As used in Taoism, the Tao refers to the way of ways, the law of laws, the ultimate reality and its structure ... Lao-tzu urges the ruler ("the sage") to refrain from acting, to accept the good with the bad, to let the people pursue their own actions. In the Taoist view, harmony can be achieved only through strife or competition.

Lao Tzu (c. 600 BC), by

James A. Dorn,

The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism, 15 Aug 2008

Biographical essay focusing on Laozi's teachings

In the Tao Te Ching ("The Classic of the Way and Its Virtue"), Lao Tzu discusses the relations among the individual, the state, and nature. Like 18th-century liberals, he argued that minimizing the role of government and letting individuals develop spontaneously would best achieve social and economic harmony. In 81 short chapters (less than 6,000 words), Lao Tzu sets out his vision of good government and a good life. At the center of his thoughts were the principle of wu-wei (nonaction or nonintervention) and the notion of spontaneous order.

Liberty and Small Government in Tao te Ching, by Luke Hankins, 22 Apr 2014

Presents selections from the

Dào Dé Jīng, examining some of the seeming paradoxes of Daoist philosophy

"When the Master governs," wrote Lao Tzu, "the people/are hardly aware that he exists." This passage, like many in the ancient Chinese wisdom poem Tao te Ching (pronounced dow deh jing), written in the 6th century BC, expresses the paradoxical view of passivity as the most effective political power ... Tao means "way" or "path," and Tao te Ching means something like "The Book of the Manifestation of the Way" or "The Book of the Virtue of the Way" ... Tao te Ching views laissez-faire, small government, and non-intervention as political ideals in keeping with the Tao.

Taoism in Ancient China, by

Murray N. Rothbard,

Economic Thought Before Adam Smith, 1995

Chapter 1, section 1.10; discusses the three schools of political philosophy and then concentrates on the Daoists, covering Lǎozǐ (Lao Tzu), Zhuāng Zhōu (Chuang Tzu), Bào (Pao) Jìngyán and the historian Sīmǎ Qiān (Ch'ien)

'[I]naction' became the watchword for Lao Tzu, since only inaction of government can permit the individual to flourish and achieve happiness ... The worst of government interventions, according to Lao Tzu, was heavy taxation and war. 'The people hunger because their superiors consume an excess in taxation' and, 'where armies have been stationed, thorns and brambles grow. After a great war, harsh years of famine are sure to follow'. The wisest course is to keep the government simple and inactive, for then the world 'stabilizes itself'.

Books

Te-Tao Ching (Modern Library)

by

Lǎozǐ, 1993

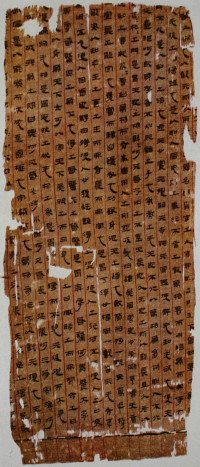

Translated and with and introduction by Robert G. Henricks; partial contents: The Ma-wang-tui Manuscripts of the

Lao-tzu and Other Versions of the Text - The Philosophy of Lao-tzu - Translator's Note - Te (Virtue) - Tao (The Way)