Reference

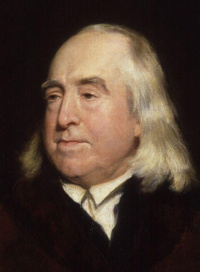

Bentham, Jeremy (1748-1832), by

T. Patrick Burke,

The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism, 15 Aug 2008

Biographical and bibliographical essay

Jeremy Bentham is known today chiefly as the father of utilitarianism. During his lifetime, [he] was famous as the proponent of a scientific approach to social reform. Born in London, the son of an attorney, Bentham was a precocious child ... In [his] time, law, judicial procedures, and life in general were governed ... by historical precedent and beliefs not subjected to critical examination. We owe much of the difference between his time and ours to Bentham ... [He] argued that a policy or procedure was in accordance with reason when it maximized utility, understood as human happiness.

Biography

Who Was Jeremy Bentham?

Hosted by the Bentham Project at University College London

Even for those who have never read a line of Bentham, he will always be associated with the doctrine of Utilitarianism and the principle of 'the greatest happiness of the greatest number'. This, however, was only his starting point for a radical critique of society, which aimed to test the usefulness of existing institutions, practices and beliefs against an objective evaluative standard. ... A visionary far ahead of his time, he advocated universal suffrage and the decriminalisation of homosexuality.

Websites

Bentham Project - UCL - London's Global University

Includes biography of Bentham, information about the project and works by and about Bentham, and other related resources

This website gives information on Jeremy Bentham and about the work of the Bentham Project. We are the world centre for Bentham Studies and our main activity is the production of the new edition of Bentham's Collected Works. We are part of UCL's Faculty of Laws.

Articles

Bentham, by

John Stuart Mill,

London and Westminster Review, Aug 1838

Opens by contrasting Bentham as a Progressive and Coleridge as a Conservative, then proceeds to examine and criticize Bentham philosophical method, and then his theories of life, law, government and utility

This, then, is our idea of Bentham. He was a man both of remarkable endowments for philosophy, and of remarkable deficiencies for it; fitted, beyond almost any man, for drawing from his premises, conclusions not only correct, but sufficiently precise and specific to be practical; but whose general conception of human nature and life furnished him with an unusually slender stock of premises. It is obvious what would be likely to be achieved by such a man; what a thinker, thus gifted and thus disqualified, could do in philosophy.

The Courts and the New Deal, Part 1, by

William L. Anderson,

Freedom Daily, Jun 2005

First part of a four-part series examining how Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal affected federal courts and other legal practices; contrasts the thoughts of Blackstone and Bentham

Perhaps it is deeply ironic that in 1776 ..., the "champion" of modern law made his own intellectual debut ... Jeremy Bentham, who sat in Blackstone's Oxford lectures as a student, penned an anonymous attack on Blackstone entitled "A Fragment on Government." "Fragment" took the opposite approach to every ideal Blackstone laid out in his writings and lectures. Government's role in society, wrote Bentham, was not to protect the innocent or to be restrained ..., but rather to have near-unlimited powers to ensure the overall happiness of society, or "the greatest happiness for the greatest number."

Libertarianism and Legal Paternalism [PDF], by

John Hospers,

The Journal of Libertarian Studies, 1980

Discusses laws "designed to protect people from themselves" arguing that in general such laws are illegitimate

In his book Principles of Morals and Legislation, the ... philosopher and legislator Jeremy Bentham divided all laws into three kinds: (1) laws designed to protect you from harm caused by other people; (2) laws designed to protect you from harm caused by yourself; and (3) laws requiring you to help and assist others. Bentham held that only the first kind of laws were legitimate ... The third class of laws, sometimes called "good Samaritan" laws, are greatly on the increase today ... Bentham argued persuasively against these laws as well; but he also condemned laws of the second kind ...

Real Liberalism and the Law of Nature, by

Sheldon Richman,

The Goal Is Freedom, 10 Aug 2007

Examines Thomas Hodgskin's introductory letter to Henry Brougham, a Member of Parliament (later Lord Chancellor), written in 1829, published in

The Natural and Artificial Right of Property Contrasted (1832)

One system looks on the legislator as an ally, in enforcing the laws of nature ... Mr. Locke's view is, in my opinion, more correct than Mr. [Jeremy] Bentham's, though at present among legislators, and those who aspire to be legislators, the latter is by far the most prevalent. Practical men universally adopt it; for they always decree, and never inquire into the laws of nature. The prevalence of Mr. Bentham's opinion, makes it necessary to illustrate and enforce that of Mr. Locke, in so far as it is limited to asserting that a right of property is not the offspring of legislation.

Reasoning on the Nature of Things, by

Clarence B. Carson,

The Freeman, Feb 1982

Discusses how natural law doctrines were repudiated by utilitarians, why natural rights are important from an economic viewpoint, how the rights to life, liberty and property can be construed and what the author understands as the "social contract"

Some thinkers repudiated, denounced, and denigrated the very idea of natural laws. The utilitarians were among the more outspoken of these. Jeremy Bentham said of those who believed in natural law that they "take for their subject the pretended law of nature; an obscure phantom, which in the imaginations of those who go in chase of it, points sometimes to manners, sometimes to laws; sometimes to what law is, and sometimes to what it ought to be." ... In his efforts at legal reforms, Bentham encountered natural law exponents as an obstacle and simply repudiated the theory.

Related Topics:

Government,

Law,

Liberty,

John Stuart Mill,

Philosophy,

Property Rights,

Ronald Reagan,

Rights,

Adam Smith,

Socialism,

Society

Security Cameras' Slippery Slope, by

Gene Healy,

The Washington Examiner, 11 May 2010

Discusses the use of surveillance cameras in New York City, in London and elsewhere in the United Kingdom and in the United States, as well as drones by British police

In 1787, utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham dreamed up "a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind," the "Panopticon"—a building designed so that all the occupants could be monitored from a central point, "always feel[ing] themselves as if under inspection." This would work well in prisons, Bentham thought, but also in schools and factories. There's more than a little of [his] vision in Britain's burgeoning surveillance state. The Panopticon's no panacea, though ... An internal study by London police showed that for every 1,000 cameras, fewer than "one crime is solved per year" ...

Sowell and Spying, by

William L. Anderson, 9 Feb 2006

Criticizes Sowell for his 7 Feb 2006 column titled "Point of no return" in which he defended the George W. Bush administration's warrantless domestic phone surveillance program on utilitarian grounds

We are opposed to such government wiretaps on the basis of principle, just as we oppose wrongful killings. Yet, Sowell defends the wiretapping, at least in part, by claiming that its harmful effects are innocuous, but that its good effects overwhelm any negative ones. To put it another way, his defense is pure utilitarianism, something that would have made Jeremy Bentham proud. But suppose that for every 100 people that the FBI kills at random, one or two might have been planning a terrorist attack, and that each attack would kill on average at least 200 people. Could we not then justify such an attack using Sowell's Benthamite logic?